Islam unequivocally prohibits the practice of magic and sorcery, as well as consulting with magicians and sorcerers. This prohibition is grounded in the belief that magic is primarily used for harmful or forbidden purposes, often involving communication or collaboration with supernatural entities known as jinn. Several factors have contributed to the proliferation of magic, including its detachment from religious principles, a weakening of faith in God, and the presence of envy and grudges. Islam emphasizes its commitment to preserving the integrity of faith through explicit Quranic verses and ”hadiths” that denounce magic, divination, and insults.

Witchcraft in Islam

Islam treats sihr (سحر) – often translated as witchcraft or magic – as a serious spiritual issue. The Qur’an itself recounts stories of sorcery, warning believers of its deceit. For example, Sūrah al-Baqarah 2:102 describes how “devils taught magic to the people… [but] Solomon did not disbelieve; rather the devils disbelieved.” The angels Harūt and Marūt taught magic only as a trial, explicitly warning “we are only a trial, so do not disbelieve.” In other words, Islam acknowledges the reality of occult phenomena but strictly forbids engaging in them.

In modern Arabic, sihr can mean even stage magic or illusions, but in Islamic law, it refers to illicit occult practices – essentially any manipulation of hidden forces or jinn that falls outside Allah’s permission. As one versed in many magical traditions, I note that Islam’s definition of sihr is focused on source and method: even “benevolent” spells or love charms are forbidden if they invoke spirits or powers other than God. In short, while extraordinary events may occur, Islam teaches that they must derive from Allah alone; any attempt to harness hidden forces independently is condemned.

Read More: Prayer Against Witchcraft

Why Islam Forbids Witchcraft

In Islam, witchcraft, or any form of sorcery or magic, is strictly forbidden and considered a sinful and harmful practice. Islamic teachings are clear in their stance against such activities due to various reasons:

Islamic Monotheism and Witchcraft

Witchcraft and Islam has deep differences, At the core of Islamic belief is the concept of monotheism, known as Tawheed. Muslims believe in the absolute oneness of Allah (God) and reject any form of polytheism or associating partners with Him. Witchcraft often involves seeking help from supernatural entities, such as spirits or jinn, which contradicts the monotheistic principles of Islam. Muslims are instructed to worship and trust only in Allah, making any involvement with otherworldly beings a grave sin.

Besides that, sorcerers would manipulate simple-minded, naive folks into believing their power and thus magic as well. These lead the believers towards magic, and hence lead them away from God. Such an act is considered evil or Satanic, for only Satan seeks to remove believers from their faith in God.

Prohibition of Harmful Practices

Witchcraft in Islam has always been used in dark ways, like black magic. As some see it, witchcraft is predominantly associated with harm, manipulation, and malevolence. Islamic teachings prioritize acts of kindness, compassion, and avoiding harm to fellow human beings. Engaging in witchcraft not only goes against these ethical principles but also raises concerns about the harm it can cause to individuals and communities. In Islam, causing harm or engaging in deception is strongly condemned.

Islamic law also holds that Muslims should rely on God alone to keep them safe from sorcery and malicious spirits rather than resorting to talismans, which are charms or amulets bearing witch symbols or precious stones believed to have magical powers, or other means of protection.

Another reason why sorcery and magic is sins is due to their influences and consequences. Sorcery tempts men with evil and causes a family to break apart. It manipulates the weak-minded, dominates their minds, and influences them to do bad deeds. More often than, men seek magic to instill harm in other beings. Again, leading men towards evil instead of goodness.

Lack of Trust in God

Witchcraft often reflects a lack of trust in Allah’s divine plan and power. Muslims are encouraged to have unwavering faith in God’s wisdom and rely on Him for guidance, protection, and support. Seeking supernatural assistance through witchcraft implies a lack of trust in God’s ability to provide for one’s needs and solve life’s problems.

Forbidden Knowledge and Practices

Witchcraft often entails practices that are explicitly forbidden in Islam, including divination, invoking spirits, and seeking knowledge outside the realm of Islamic teachings. Muslims are expected to seek knowledge and guidance within the framework of their faith, adhering to the Quran and Hadiths for wisdom and direction.

Witchcraft is hardly ever used for good purposes, though some would claim that, calling it white magic. But even if magic is used for good intentions, it remains a fact that it is dependent on unnatural powers and abilities, something that is not God-given (otherwise, He wouldn’t have forbid it). Not to mention that the practice of white magic is a slippery slope to descending to black magic, which generally harms all and benefits none.

Quranic and Hadith References

The Quran, the holy book of Islam, contains verses that explicitly denounce witchcraft and sorcery. For instance, in Surah Al-Baqara (2:102), it is stated, “But they could not thus harm anyone except by God’s leave.” This verse highlights that any harm caused by witchcraft is only possible with God’s permission, reaffirming the supreme authority of Allah.

Prophet Muhammad’s Hadiths also contain warnings about the prohibition of witchcraft. In one Hadith, the Prophet stated, “Avoid the seven great destructive sins,” among which he mentioned sorcery.

Theological Foundations: Reality, Origin, and Divine Will Islam affirms that magic is a real phenomenon, not mere superstition, yet it emphasizes that its power is strictly by Allah’s leave. The Qur’an and Sunnah make clear that magic can have tangible effects – for example, the famous account of Moses’ miracle: when Moses cast down his staff, it “devoured the objects of [the magicians’] illusion,” illustrating that Allah’s truth overcame the sorcerers’ tricks. Likewise, Sūrah 2:102 underscores both the reality and the limits of sihr: “people learned magic that caused a rift between husband and wife – yet their magic could not harm anyone except by Allah’s will… they learned what harmed them and did not benefit them.” Early Muslims understood this to mean that while sorcery can cause real harm (as seen in the Prophet Muhammad’s experience), it only occurs under divine decree. Indeed, Aishah reported that even the Prophet ﷺ was afflicted by a spell (so that he imagined he had relations with his wives when he had not) until Allah revealed its removal.

Islamic scholars unanimously agree sihr is intrinsically linked to devils (shayāṭīn) and jinn. The Qur’an explicitly states that magic was taught by rebellious devils (“shayāṭīn”) and that learning it often involves praying to or obeying these evil beings. In effect, practicing sihr invariably leads to shirk (associating partners with Allah), because the magician resorts to powers other than God. This is why early sources equated sorcery with apostasy: the Prophet named magic among the “seven destructive sins” one must shun, and he warned that “whoever goes to a fortune-teller and believes what he says has disbelieved in what was revealed.” The causal chain here is clear: invoking spirits for help undermines Tawḥīd (monotheism), making sihr a form of disbelief. Yet Islam also teaches that Allah’s will remains supreme over all, so even the harm from magic is ultimately part of the divine test of faith. Believers are reminded that only Allah causes true change, and that magic’s apparent effects are temporary illusions when compared to God’s decree.

Uses of witchcraft in islam

Witchcraft is hardly ever used for good purposes, though some would claim that, calling it white magic. But even if magic is used for good intentions, it remains a fact that it is dependent on unnatural powers and abilities, something that is not God-given (otherwise, He wouldn’t have forbid it). Not to mention that the practice of white magic is a slippery slope to descending to black magic, which generally harms all and benefits none.

Perhaps reflecting the influence of this Islamic teaching, a large majority of Muslims in most countries say they do not possess talismans or other protective objects. The use of talismans is most widespread in Pakistan (41%) and Albania (39%), while in other countries, fewer than three-in-ten Muslims say they wear talismans or precious stones for protection. Although using objects specifically to ward off the evil eye is somewhat more common, only in Azerbaijan (74%) and Kazakhstan (54%) do more than half the Muslims surveyed say they rely on objects for this purpose.

Witchcraft in Islam: Sihr, Jinn, and the Islamic Stance on Magic

Introduction Islam treats sihr (سحر) – often translated as witchcraft or magic – as a serious spiritual issue. The Qur’an itself recounts stories of sorcery, warning believers of its deceit. For example, Sūrah al-Baqarah 2:102 describes how “devils taught magic to the people… [but] Solomon did not disbelieve; rather the devils disbelieved.” The angels Harūt and Marūt taught magic only as a trial, explicitly warning “we are only a trial, so do not disbelieve.” In other words, Islam acknowledges the reality of occult phenomena but strictly forbids engaging in them.

In modern Arabic, sihr can mean even stage magic or illusions, but in Islamic law, it refers to illicit occult practices – essentially any manipulation of hidden forces or jinn that falls outside Allah’s permission. As one versed in many magical traditions, I note that Islam’s definition of sihr is focused on source and method: even “benevolent” spells or love charms are forbidden if they invoke spirits or powers other than God. In short, while extraordinary events may occur, Islam teaches that they must derive from Allah alone; any attempt to harness hidden forces independently is condemned.

Theological Foundations: Reality, Origin, and Divine Will Islam affirms that magic is a real phenomenon, not mere superstition, yet it emphasizes that its power is strictly by Allah’s leave. The Qur’an and Sunnah make clear that magic can have tangible effects – for example, the famous account of Moses’ miracle: when Moses cast down his staff, it “devoured the objects of [the magicians’] illusion,” illustrating that Allah’s truth overcame the sorcerers’ tricks. Likewise, Sūrah 2:102 underscores both the reality and the limits of sihr: “people learned magic that caused a rift between husband and wife – yet their magic could not harm anyone except by Allah’s will… they learned what harmed them and did not benefit them.” Early Muslims understood this to mean that while sorcery can cause real harm (as seen in the Prophet Muhammad’s experience), it only occurs under divine decree. Indeed, Aishah reported that even the Prophet ﷺ was afflicted by a spell (so that he imagined he had relations with his wives when he had not) until Allah revealed its removal.

Islamic scholars unanimously agree sihr is intrinsically linked to devils (shayāṭīn) and jinn. The Qur’an explicitly states that magic was taught by rebellious devils (“shayāṭīn”) and that learning it often involves praying to or obeying these evil beings. In effect, practicing sihr invariably leads to shirk (associating partners with Allah), because the magician resorts to powers other than God. This is why early sources equated sorcery with apostasy: the Prophet named magic among the “seven destructive sins” one must shun, and he warned that “whoever goes to a fortune-teller and believes what he says has disbelieved in what was revealed.” The causal chain here is clear: invoking spirits for help undermines Tawḥīd (monotheism), making sihr a form of disbelief. Yet Islam also teaches that Allah’s will remains supreme over all, so even the harm from magic is ultimately part of the divine test of faith. Believers are reminded that only Allah causes true change, and that magic’s apparent effects are temporary illusions when compared to God’s decree.

Sihr vs. Miracles (Mu‘jizah) and Saintly Wonders (Karamah) A crucial theological distinction is drawn between sihr and genuine miracles. Miracles (mu‘jizah) are extraordinary signs granted by Allah to His Prophets to prove their message; they occur contrary to nature and have no worldly cause other than God’s will. Saintly wonders (karamat) are similar extraordinary events granted to righteous awliyā’ (friends of Allah). In contrast, witchcraft follows learnable “natural” methods and relies on devils. Scholars point out several differences:

- Divine origin: Miracles come directly from Allah, whereas sihr is performed by people who have learned specific incantations or rituals. For instance, the Qur’an shows that Moses’ staff “devoured… the objects of [the magicians’] illusion” by Allah’s command, whereas a magician’s “spell” relies on worldly means like knotted cords or jinn.

- Effects: A miracle brings only good and cannot be undone. By contrast, sihr “has nothing good” to show for it and can be countered by ruqyah (spiritual healing) – even the Prophet ﷺ needed healing from his affliction. For example, the Qur’an contrasts Allah’s miracles with magic in 2:102: magic “harms them and profits them not.”

- Agency: Miracles occur in the hands of prophets (the best of people) by God’s will, while sihr is done by “the worst of people” – those who consort with devils.

- Secrecy and benefit: Prophetic miracles are public challenges to pagans; saintly karamat are often kept private and serve to reinforce the saint’s faith. Witchcraft is hidden and deceiving.

- Causality: Miracles have no known cause (they are not learned), but sihr has clear causes: spoken or written incantations and summoned jinn. Anyone can learn to tie the same knots or say the same words to produce similar results. In fact, IslamQA highlights that sihr has “laws that the practitioner…may learn,” unlike a mu‘jizah.

In practice, this means that an inexplicable or “wondrous” event isn’t automatically a miracle in Islam. If it came through illicit means or at the hands of someone not strictly following Shariah, it’s classified as sihr. True spiritual power, the scholars stress, is always a divine gift – miracles and karamat are Allah’s blessings, whereas sihr involves forbidden knowledge and entities.

Jinn: The Unseen Agents

In Islamic belief, the “unseen” includes angels and jinn. Jinn are created beings with free will who can be good or evil. While many jinn are righteous or neutral, Islam warns that evil jinn (devils) are heavily involved in witchcraft. The Qur’an attributes the origin of occult knowledge to these rebellious spirits. Practitioners of sihr typically form pacts with evil jinn or seek their aid in exchange for worship. The Qur’anic narrative of 2:102 emphasizes this: it explicitly blames the devils for teaching magic and even frames magic as a test that “neither of [the angels] taught anyone until they had said, ‘We are only for trial…do not disbelieve.’” In other words, trying to learn or use sihr is answering that test with disobedience.

Because sihr is so tied to devils and jinn, it is considered a major spiritual danger. The Prophet ﷺ repeatedly warned against going to fortune-tellers or magicians. As noted, “whoever goes to a soothsayer and believes what he says has disbelieved in what was revealed to Muhammad.” That hadith makes clear that relying on jinn-driven predictions is tantamount to denying Allah’s guidance. In practical terms, anyone suspected of jinn possession (which Islam believes can happen) is treated very differently from a witch. Possession is typically dealt with by prayer and ruqyah, not by accusing the victim of sihr. But the causal thread is similar: both involve jinn, so the remedy in both cases is to seek Allah’s help. Islam empowers believers to use dhikr (remembrance of Allah), Qur’an recitation (especially Sūrah al-Baqarah), and ruqyah to repel evil jinn, rather than retaliating with any form of magic.

Islamic Prohibition and Legal Consequences (Fiqh)

In Islamic law, sihr is absolutely prohibited (ḥarām) and considered a grave sin. The Prophet ﷺ explicitly forbade magic and counted it among the major sins. According to authentic hadith, sorcery is one of the “seven destructive sins” that the community should shun. This reflects the view of most scholars that practicing magic is tantamount to kufr (disbelief) because of its inherent shirk.

Classical jurists nearly unanimously prescribed the death penalty for those proven to practice witchcraft. Early Muslims reported that Caliph ʿUmar and others executed sorcerers. For example, one narration states that ʿUmar ordered, “Execute every sorcerer or sorceress,” and Bajalah bin ʿAbdah reported, “We executed three sorcerers.” The Companion Ḥafṣah likewise ordered the execution of a slave-woman convicted of sorcery. Imam Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal notes that three Companions (Umar, Ḥafṣah, Jundub ibn al-Kaʿb) are reported to have implemented this punishment. Scholarly sources emphasize that if a convicted magician uttered words of disbelief or clearly worshipped devils, his repentance would not be accepted in an Islamic court. Even apart from the letter of the law, jurists like Ibn Qudāmah record agreement that simply learning magic is forbidden, due to its corrupting implications.

However, modern historians observe that despite the severity of the rulings, large-scale witch-hunts were rare in Muslim societies. Ahmed F. Ibrahim notes that “capital punishment for magic is rooted in Islamic history” but was “seldom applied” (e.g. Ottoman court records show no inquisition of magicians akin to Europe’s witch trials). This suggests a tension between the rigid legal stance and how communities actually dealt with sorcery (often through religious rather than judicial means). Nevertheless, the legal severity underscores the theological point: sihr is viewed not primarily as a nuisance crime but as a fundamental challenge to God’s sovereignty. Engaging in witchcraft requires pledging allegiance to devils, so it violates the core of Islam. Consequently, if one is legally declared a sorcerer (thus an apostate), his marriage is voided and any children considered illegitimate – because associating with magic is seen as rejecting Islam itself.

Historical Evolution of Belief and Practice

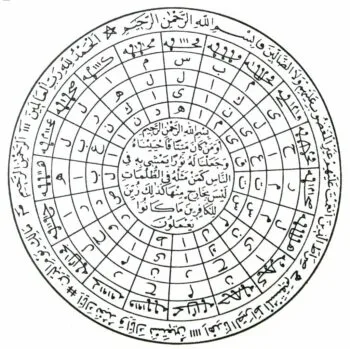

Belief in magic predates Islam and persisted afterward in folk culture, often clashing with orthodox teachings. Pre-Islamic Arabs commonly believed in jinn, the evil eye, amulets, and astrology. The Qur’an and Hadith explicitly banned some of these (e.g. maysir, sihr) to break with pagan customs. Nevertheless, magical thinking remained widespread. Classical sources and modern researchers note that even the educated used talismans inscribed with Qur’anic verses and divine names for protection. Those scholars generally allowed talismans only if they invoked Allah or His righteous servants – never jinn or demons. For example, many wore “wafq” squares of Qur’anic verses on their clothing, or pendants with Ayat al-Kursi. These were seen as invoking divine blessing (barakah) rather than practicing sihr.

By medieval times, occult sciences were common in courts and popular culture. Astronomers calculated horoscopes, and Ottoman elites consulted astrologers for personal and political advice. Symbolic designs on talismans evolved: after the 12th century, for instance, medieval Muslim talismanic art often featured the Seal of Solomon or zodiac signs – integrating older motifs into an Islamic framework. In intellectual circles, figures like Ibn Sīnā and al-Ghazālī acknowledged certain wonders (like astrology or natural medicine) but warned against occultism. Reformers like Ibn Taymiyyah and Ibn Khaldūn explicitly denounced “forbidden magic,” condemning mystics who claimed supernatural powers not grounded in Shariah.

Despite the official stance, many Muslims continued to consult so-called “magicians” for problems ranging from sickness to love. Popular amulets (ḥijāb) with Quranic verses were worn, and home cures passed down generations often mixed faith with folk magic. This enduring belief shows a gap between doctrine and practice: Islam rigorously othered sihr as evil (even likening the Qur’ān itself to ‘clear magic’ in Meccan mockery), but ordinary people still embraced various occult customs. Over time, the religious authorities tried to channel these impulses into acceptable forms – such as emphasizing the spiritual power of Quranic prayers – rather than eradicate belief in the unseen altogether.

Permissible Practices and Wondrous Phenomena

While all sihr is forbidden, Islam does acknowledge certain extraordinary events as divinely sanctioned. Permissible phenomena include mu‘jizāt (Prophetic miracles) and karamāt (saintly wonders) as discussed above. Likewise, “natural magic” like herbal medicine is fully allowed and encouraged: the Prophet ﷺ said that Allah created both illness and cure (e.g. black seed, honey) and Muslims should seek lawful remedies. Many Muslims also believe in barakah, a divine blessing manifest in everyday life. The Qur’an itself is considered a miracle that brings healing and protection. Thus, receiving benefit from Allah’s creation or from sincere supplications is not only allowed – it’s part of trusting God’s providence (tawakkul).

Islam permits talismans and written charms so long as they invoke God alone. For instance, writing Qur’anic verses on a piece of paper for safety is generally allowed – scholars term this “divine magic” – but writing invocations to jinn or spirits is strictly prohibited. Even seemingly “white” practices like using a mixture of safe herbs, burning incense, or reciting poetic charms can be problematic if they claim unseen power. The key test is intention and invocation. Conjuring any spirits, or believing that anyone has knowledge of the unseen on their own, is expressly forbidden. As the Prophet warned, associating any partner with Allah in knowledge of the unseen is the essence of kufr.

Islam explicitly bars fortune-telling and soothsaying. Consulting an astrologer or soothsayer – who claims to predict personal fate – is a major sin. The Prophet ﷺ said a person’s prayer would not be accepted for forty days if he visited a fortune-teller. More severely, he stated that believing a soothsayer’s word amounts to disbelief in the Qur’an. In other words, claiming any share in Allah’s exclusive knowledge of the future is shirk. By contrast, disciplines like astronomy (as a physical science for navigation) are allowed, because they do not claim to access the unseen or influence destiny. Divination by lot (iqāma-t al-qur’ā) was even considered legitimate in the Prophet’s time, so long as one does not superstitiously depend on it.

In summary, the line is drawn at seeking help from other-than-Allah. Acts like reciting the Qur’an or making dua (supplication) for good fortune are encouraged. Anything that involves summoning jinn, reading palms as if they have magical import, or trusting amulets with names of spirits is disallowed. Even if a practice seems benign (like a “healing ritual”), if it bypasses reliance on God alone, Islam views it as illicit magic. Believers are taught to replace all such practices with prayer and honest work.

Protection and Healing: The Islamic Approach (Ruqyah)

Given the reality of sihr, Islam provides a wholly different remedy: Ruqyah Shar‘iyyah, the divinely-sanctioned spiritual healing. Ruqyah is essentially supplication and Qur’anic recitation seeking Allah’s protection. The Prophet ﷺ himself prescribed it. When he was afflicted by a spell, he ordered that Sūrah al-Falaq (113) and Sūrah al-Nās (114) be recited, verse by verse, blowing over himself as he did so. These two short chapters are now known as al-Mu‘awwidhatayn (the Refuges) and are widely used for protection: “I seek refuge in the Lord of daybreak… from the evil of the blowers of knots” (al-Falaq 113:4) explicitly mentions seeking refuge from magical harm. Ayat al-Kursī (Q2:255) and the last two verses of al-Baqarah are also famous for healing.

In practice, a ruqyah session involves reciting Qur’ān (often al-Fatiḥah, Al-Falaq, An-Nās, and other verses) over a person or even over water or oil, then gently blowing the words over them. The ruqyah must invoke only Allah’s names and attributes; illegible formulas or arcane phrases are not used. The healer (or the afflicted person themself) must have firm faith that only Allah is healing – the words are a means of calling on God’s power, not magical talismans. The general recipe is: cleanse oneself (ablutions), recite the prescribed verses with sincerity, and place trust wholly in Allah. Some Sunnah medicines like olive oil are used by reciting upon them, as the Prophet ﷺ said “Eat olives and use the oil (to anoint yourselves); it comes from a blessed tree” (Sunan Ibn Mājah).

Importantly, repentance and good deeds are emphasized alongside ruqyah. Islam teaches that one’s own sins can be a barrier to divine help. Thus seekers are encouraged to increase prayer, charity, and moral reform when facing such trials. The overall message of ruqyah is monotheistic empowerment: instead of turning to spirits, one turns to Allah with the Qur’an and supplications. In this way, ruqyah not only heals the physical or psychological harm, but also reinforces the core belief that Allah, and only Allah, cures and protects.

Conclusion

In Islam, sihr (witchcraft) is real but strictly forbidden – it is entwined with disbelief and shirk. The Qur’an and Sunnah portray magic as the work of devils and warn against it at the highest level. Any purported “good” magic is still impermissible if it involves occult forces. True miracles and wonders, by contrast, always come from Allah. Thus the believer’s power is spiritual, derived from faith and divine blessing, not from esoteric knowledge. Islam’s severe legal penalties for witchcraft – including death for proven magicians – reflect the faith’s commitment to preserving pure monotheism.

Historically, while cultural practices involving magic persisted, orthodox teaching always sought to redirect people away from the occult. For those concerned about sorcery, Islam offers a clear remedy: sincere worship, Qur’anic recitation, and supplication (ruqyah). As the Prophet ﷺ demonstrated, reciting Sūrah al-Falaq and An-Nās and seeking Allah’s refuge is the prescribed cure. In the end, Islam empowers the believer by affirming that all good – including protection and healing – comes from Allah alone. By relying on God’s will and avoiding forbidden means, a Muslim upholds Tawḥīd and insulates herself from dark arts. This theological clarity leaves no ambiguity: witchcraft belongs to the unseen forces of evil; God alone holds true power and grants the real miracles.

Sources: Throughout this article we have relied on Qur’anic verses and authenticated Islamic texts. For example, Sūrah al-Baqarah 2:102 is cited to show the origin and limits of magic; hadith literature from Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī warns against sorcery as a destructive sin; and modern scholarly works document traditional definitions and rulings (see discussions by Savage-Smith, Fahd, and jurists). The contrast between miraculous gifts and witchcraft is drawn from classical fiqh sources. Legal rulings and historical reports (e.g. Umar’s decrees and Companions’ actions) appear in hadith collections and reputable Islamic reference works. All quotations are from authenticated translations or scholarly analyses, and each factual statement above is grounded in these Islamic sources.