Witches were burned in parts of Europe between the 15th and 17th centuries because witchcraft was redefined as heresy—a direct alliance with the Devil—making it one of the gravest crimes in Christian society. In regions such as the Holy Roman Empire and Scotland, burning was believed to purify the soul and prevent the witch’s spirit from returning, while also serving as a public warning. Although witch trials history shows that England and Colonial America favored hanging, the fear of Satan’s influence, combined with religious rivalries and harsh legal systems, made burning a common and symbolic punishment across much of continental Europe.

The Persecution of Witches

Between 1450 and 1750, Europe and Colonial America entered one of the darkest chapters in history: the witch hunts. Fueled by fear, religious upheaval, and social instability, these persecutions claimed an estimated 35,000–60,000 lives. Contrary to popular belief, witches were not always burned—execution methods varied widely by region. But whether by fire, rope, or blade, the core question remains: Why were witches burned at all?

To understand this, we must explore the tangled roots of law, religion, superstition, and human nature itself.

The Shadowed Era: When Fear Took Hold

Fear is a potent fuel for persecution. In a time when famine, disease, and war were constant companions, communities often sought a scapegoat. Ancient laws in Egypt, Babylonia, and even biblical scripture condemned sorcery, laying the groundwork for later centuries of prosecution. The Hebrew Bible’s command, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”, became a rallying cry in medieval Europe.

Witch hunts were not born in the Early Modern period—they escalated there. Economic instability, the Counter-Reformation, and wars like the Thirty Years’ War created a climate ripe for suspicion. Misfortunes were rarely seen as random; instead, they were blamed on malevolent forces—forces supposedly embodied in witches.

The Shifting Sands of Law: From Crime to Heresy

What turned local superstition into a continent-wide purge? The key was law and theology intertwining. By the late 15th century, witchcraft had been reframed as diabolical heresy—a pact with the Devil. This wasn’t just petty malefice; it was treason against God.

The publication of the Malleus Maleficarum in 1487 provided inquisitors with a legal and theological manual for detecting, trying, and condemning witches. Torture became an accepted means of extracting confessions, and safeguards for the accused vanished.

Different regions saw different outcomes:

- German states burned more witches than any other area, partly due to fragmented legal systems and the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1530), which allowed judge-initiated prosecutions.

- Spain and Italy, under inquisitorial courts, were surprisingly skeptical and saw fewer executions.

- England and Colonial America hanged their accused witches rather than burn them.

Faith, Power, and Persecution

Religion played a central role. As the Catholic Church fought the Protestant Reformation, witch trials became a grim form of “spiritual competition.” Both Catholic and Protestant authorities sought to prove their divine legitimacy by demonstrating their ability to root out Satan’s influence.

In Protestant strongholds like Germany and Switzerland, trials were particularly intense. In contrast, solidly Catholic countries like Spain and Italy saw far fewer executions—suggesting that competition, rather than mere belief, was a major driver.

Life’s Hardships and Society’s Scapegoats

The formula for a witch hunt was simple: fear + a trigger = a scapegoat.

If crops failed, disease struck, or a child died, suspicion often fell on the outsider, the poor widow, or the outspoken midwife. In Salem Village, local feuds over land and church leadership intertwined with accusations. In Germany, wealthy individuals accused of “greedy practices” or “dragon ownership” became targets—suggesting that witchcraft accusations sometimes masked economic or political motives.

Most accused were women—often elderly, poor, and socially vulnerable. In New England, 78% of accused witches between 1620 and 1725 were women over forty.

The Fiery Truth: Burning Was Not Universal

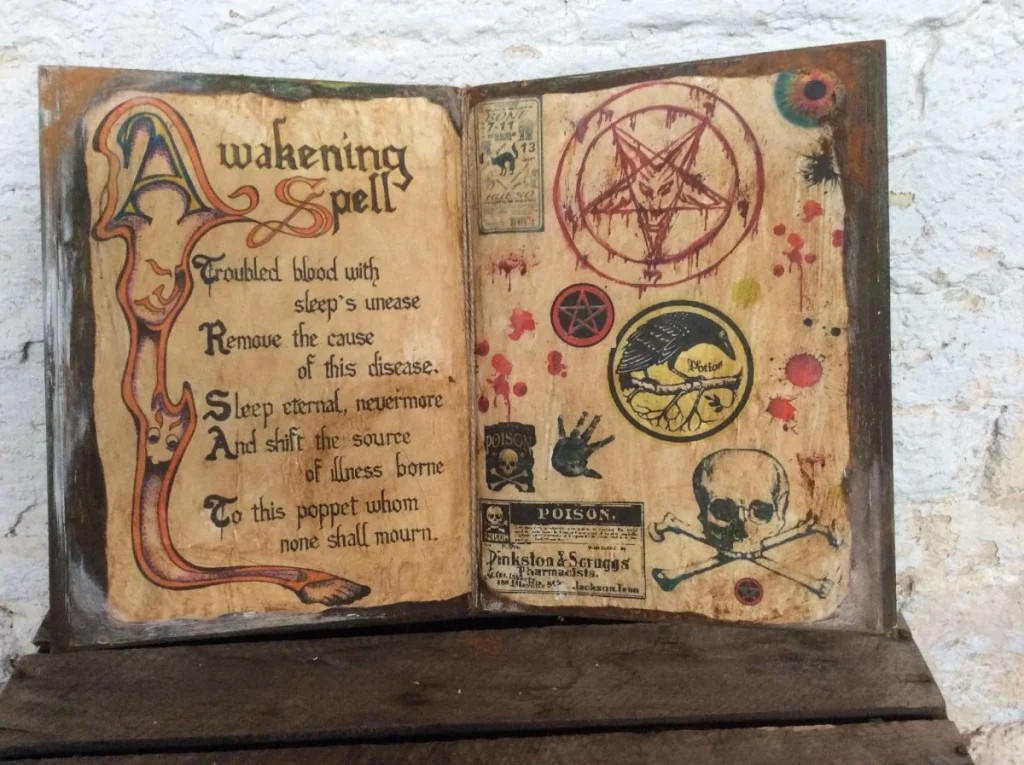

The image of witches bound to a stake, flames licking at their feet, is powerful—but misleading.

- England & Colonial America: Hanging was the standard punishment for witchcraft.

- Scotland: Victims were strangled before their bodies were burned.

- Continental Europe: Burning was common, especially in the Holy Roman Empire—but often after hanging or beheading, with fire used to prevent “postmortem sorcery.”

The myth that “nine million witches” were burned is also false—real numbers are closer to 30,000–60,000 over three centuries. Still horrific, but far from the exaggerated folklore.

Echoes in Time: Lessons from the Witch Hunts

By the 18th century, skepticism about spectral evidence, the waning of inter-church rivalry, and the rise of scientific thinking ended large-scale witch trials. Laws against witchcraft were repealed, replaced by measures against fraudulent magical claims.

Yet the pattern endures. The witch hunts remind us that fear, mixed with misinformation, creates dangerous scapegoats. Today, the term “witch hunt” is often misused in politics, but its historical weight warns us of the perils of hysteria, prejudice, and unchecked authority.

Closing Reflection

Witches were burned not merely because of superstition, but because fear, power, and politics weaponized belief. The flames that consumed them were stoked by law, faith, and human need for a simple explanation to complex problems.

And while the pyres of the past are gone, the impulse to “burn the witch” lives on—sometimes in courts, sometimes in headlines, sometimes in whispers. Remembering this history is not just about honoring the dead—it’s about ensuring we don’t repeat the same dark dance of fear and fire.